2025: The Rise of Robot Money

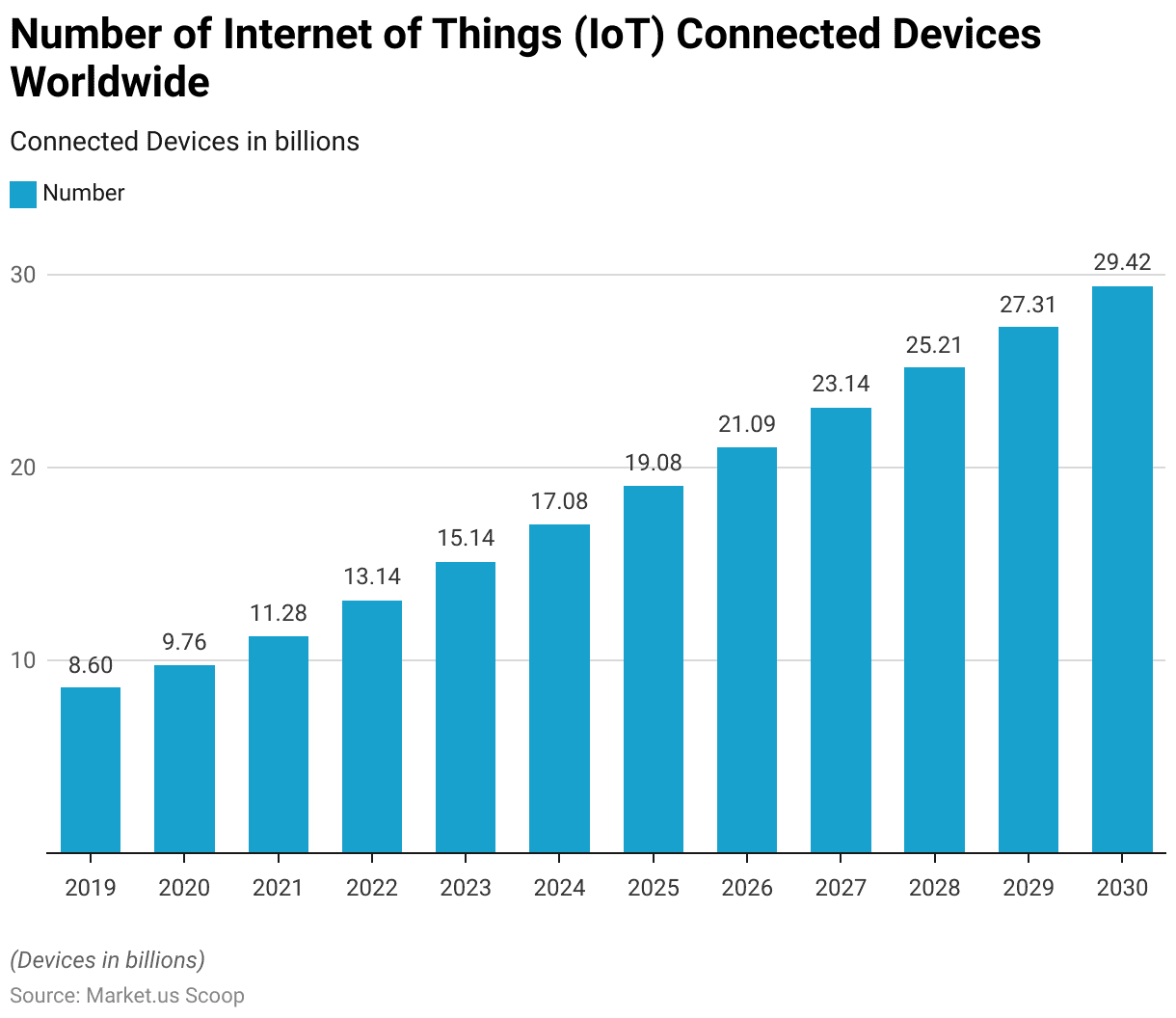

We are in the future where there are more machines than humans.

Already.

These are hardware devices connected to the Internet. You could add on the number of phones, sophisticated AI agents, and various enterprise automations to get an even larger number.

While there are 8 billion people, machines outnumber and outwork us.

What are machines? They are the shadows on the wall of the cave, imagined and built by prior generations of workers and inventors. They are our own reflections, caught in automaton purgatory, producing the things we humans desire. They are us.

The Internet is for robots, and crypto is robot money.

But the story of *Robot Money* — now capitalized for importance — is growing. In a world of the machine economy, our key question is about what becomes valuable in a new financial services industry. To whom does the value flow? Does it go to the worker? To the technology inventor? To the capitalist?

Source: Generative Ventures, Research Paper

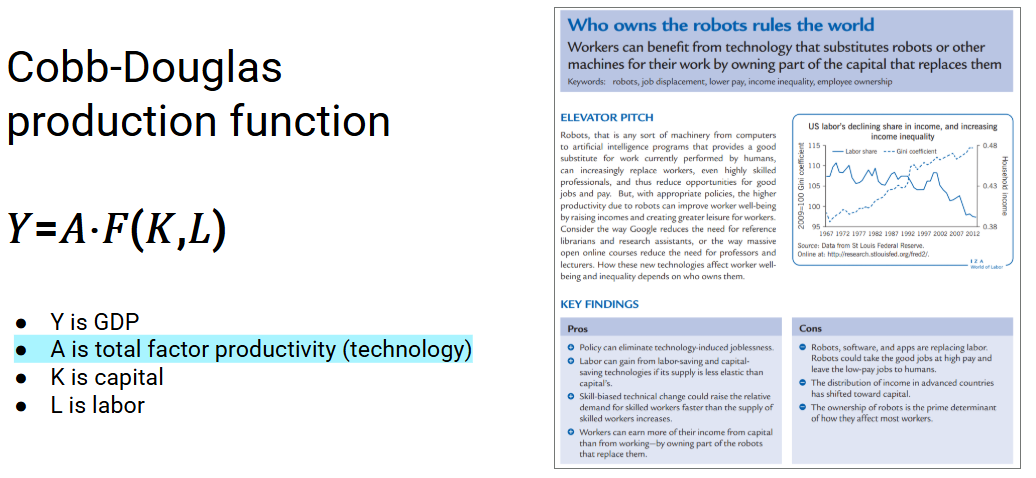

Economists model GDP with a production function composed of K (capital), L (labor), and A (the technology residual). This Cobb-Douglas production function is the simplest way to think about GDP and its growth. We dug into the research on the topic, and most economists seem to agree — “Who owns the robots, rules the world”.

At least from the perspective of getting rich.

Source: Research Paper

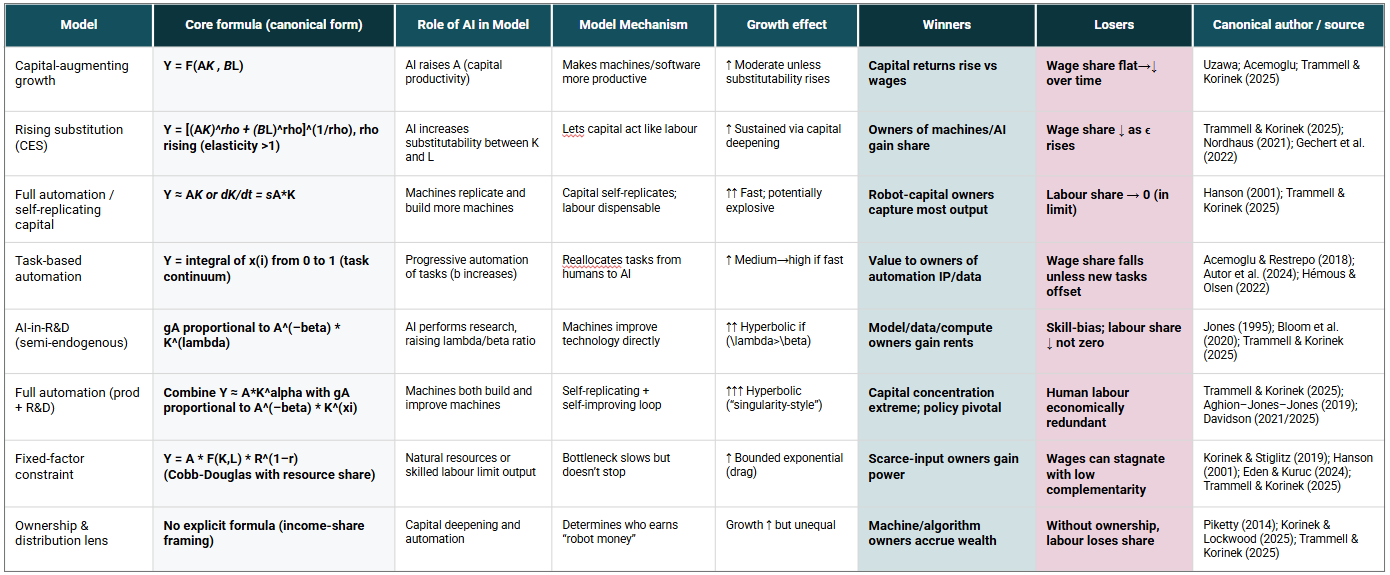

There are multiple ways to enhance the model. We have summarized the academic research above.

One could think about AI augmenting the effectiveness of both capital and labor in different ways, rather than as a total factor. Or, you can think about human goods as a premium craft, compared to mass-produced intelligence from digital inference. Or, you can build around ideas for self-replicating robots that become a substitute for workers.

While it is not always clear what exactly happens to wages, the overall trend is towards human productivity becoming a less meaningful economic input, and value flowing to the owners of machines and digital capital.

Whoever owns the robots, rules the world.

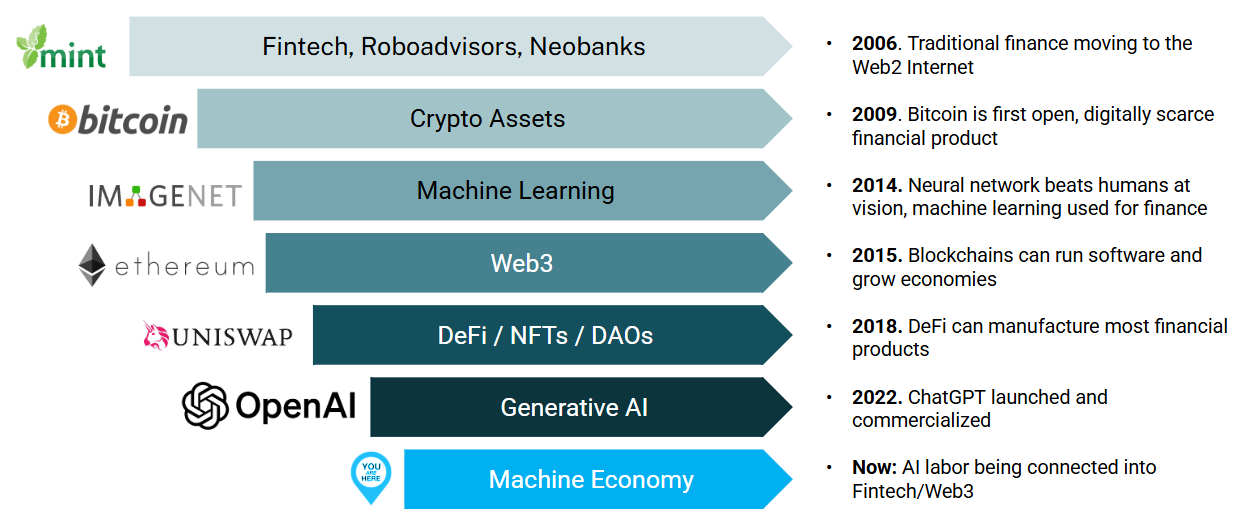

The impact on GDP is already happening. In fact, it is a continuation of 15 years of digital transformation of our economy and financial assets.

On the financial side, it all started with the distribution of financial products through the Web2 Internet, initially within roboadvisors, digital lenders, and neobanks. Innovation moved on to the manufacturing of financial products on crypto-native blockchain rails. Today, most financial products — from payments, to savings, to investments, to trading, to lending, and insurance — can be generated by users from open-source, global, decentralized protocols running onchain.

When we look at the economy, the turning point happened in 2014, as neural networks beat human vision in the Imagenet competition. Ever since, machine intelligence has been defeating humans on an increasing variety of tasks. Many of these tasks, like coding, design, writing, music generation, and video editing, are commercial and are jobs held by people today.

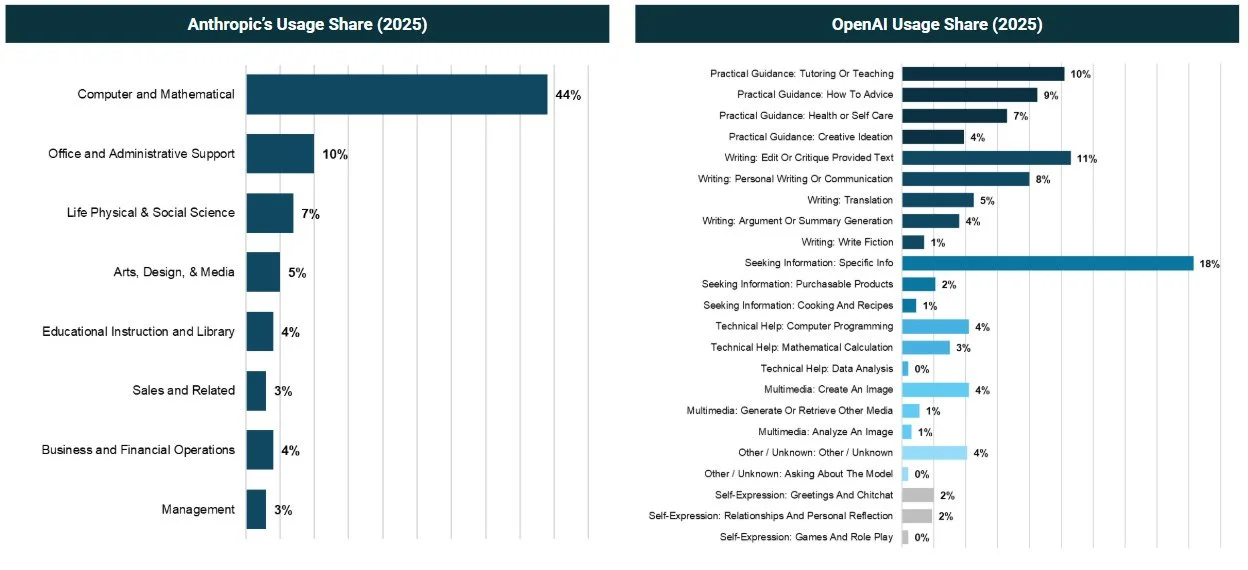

Take a look at the statistics of usage for the main LLMs above.

Anthropic is showing 44% of its usage on computer and mathematics tasks. It is effectively an enormous hardware brain churning out new code and computation for downstream software apps. The AIs are not building new AIs yet — rather, as a more advanced synthetic intelligence, they are birthing the primitive synthetics of SaaS applications.

OpenAI is eating Google, which explains why Google has been on a push with its Gemini models and TPU chip architecture. Information retrieval and processing — the core human skill of *thinking* — is being subsumed by ChatGPT. The robot is teaching, writing, translating, creating images, and playing therapist.

These are all jobs to be done, obviously. They are all economic tasks.

And what do we expect to happen from this?

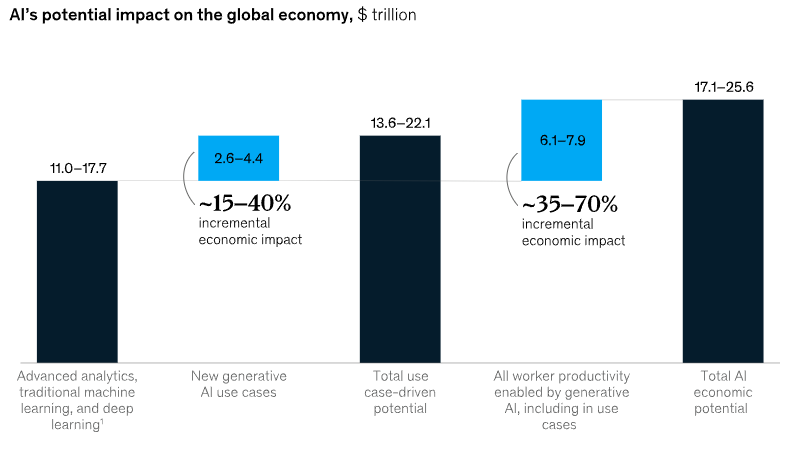

Source: McKinsey

We have been able to use this McKinsey analysis for a few years now. It shows the GDP impact of AI applied to the next decade. There is about $15 trillion that we can expect out of incremental AI use-cases. You can think of this as feature applications or companies. Another $7 trillion of GDP comes from “all worker productivity”, leading to a total of over $20 trillion in AI economic impact.

What is never said is whether this gets added or subtracted from the current numbers. Do people get replaced, and therefore this is subtracted from human GDP, or do people get enhanced, and therefore this is added from human GDP?

What a mystery! No way to tell, right? Well actually.

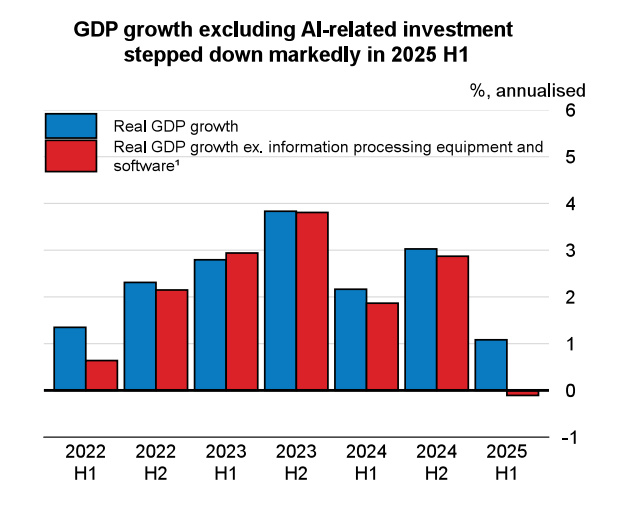

Recent US real GDP has gone negative if you pull out investments and gains from the technology industry. Nothing is really growing outside of the machine economy.

Whether the cause is political, social, or more generally related to the business cycle doesn’t really matter. Everyone is in the same boat. Population growth issues (less people with new generations), combined with rising national populism (collapse of institutionalism and neoliberalism), and a faltering monetary fiat system (dollar inflation to reduce runaways debt) are all symptoms of the natural limits of the human economy.

But the non-human economy is growing!

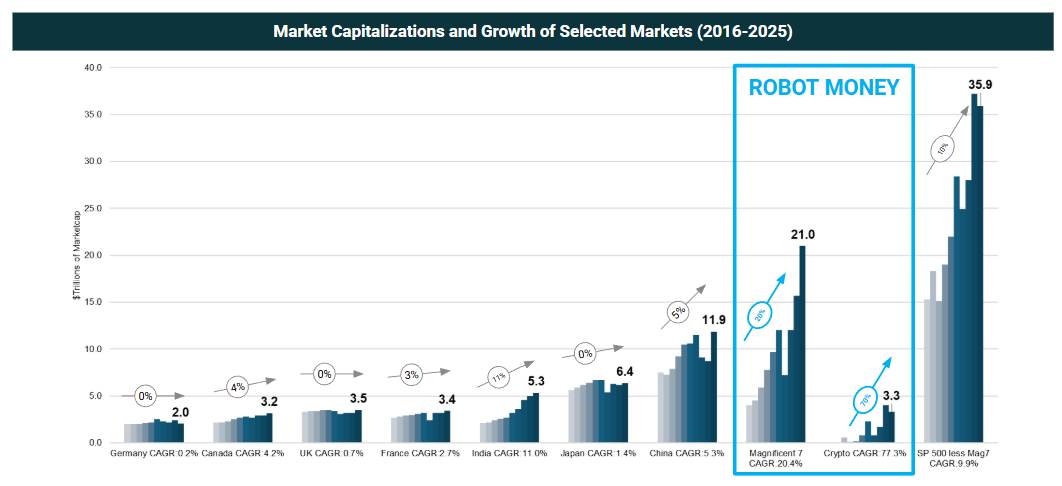

That brings us to this chart.

Source: McKinsey, Zion Market Research

This is a crazy, crazy, super insane chart.

We plot the market capitalization of several geographies, measured in the trillions, against each other. Additionally, the trend is shown over time, with a bar for each year. So for example, Germany’s capital market is worth $2 trillion, and it has grown 0.2% between 2016 and 2025.

Canada is at $3.2T after growing at a 4% CAGR. The UK grew at a 0.7% CAGR to arrive at $3.5T of marketcap. France saw 2.7% growth per year, and sits at $3.4T of marketcap. There is effectively *nothing* happening here at all.

Let me repeat that. There is almost nothing happening in these markets but maintenance of the past. You might as well have invested in a treasury note and let it ride at 3% per year, and you would have created more value.

As we move to the right, India and China are showing 5-10% CAGRs, and net market cap created over the time period is about $3T and $5T in value. These are nations with immense opportunity to reach US GDP per capita and concentrate production.

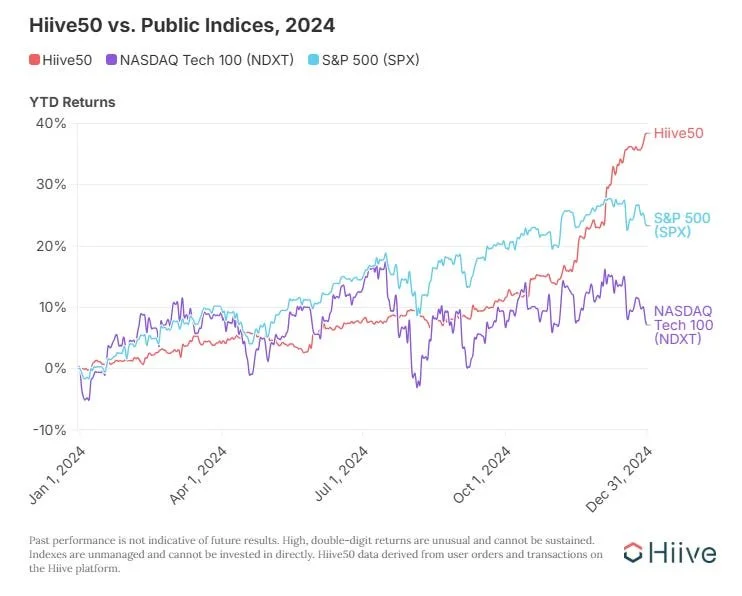

Now that you understand the scale, consider what we categorize as robot money.

The magnificient 7 companies, representing technology and AI, have added about $17 trillion of marketcap at a rate of 20% per year.

The crypto asset market, representing modern financial rails, has added $3T over the same time period, at a 70% CAGR.

Crypto is the size of the UK, built in less than a decade from nothing. Meanwhile, the UK generated no net new material enterprise value. This is effectively the same for Germany and France.

On the AI side, for full context, the overall US equities market without the Mag7 sits at $35T, having grown at a 10% CAGR. Given the size of the market, and the $20T of value it added, the outcome is impressive.

But if we look to the future, the picture is clear. Digital assets are the size of the equities market of an entire first world nation state. Tech companies are the main source of economic growth. Robot money is where the two meet.

The Shape of the Frontier

I am being broad in my descriptions on purpose. It is meant to stimulate your novelty search through this fog.

What symptoms do we have at the micro level that this is happening?

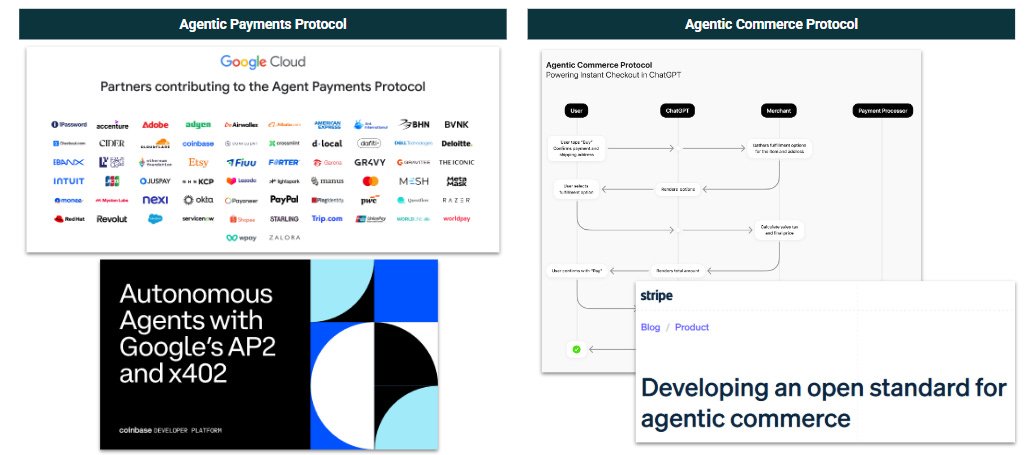

We have discussed in detail the rise in agentic payments protocols and the competition between Google + Coinbase and Stripe + OpenAI to land this opportunity ahead of the market. More detail can be seen here.

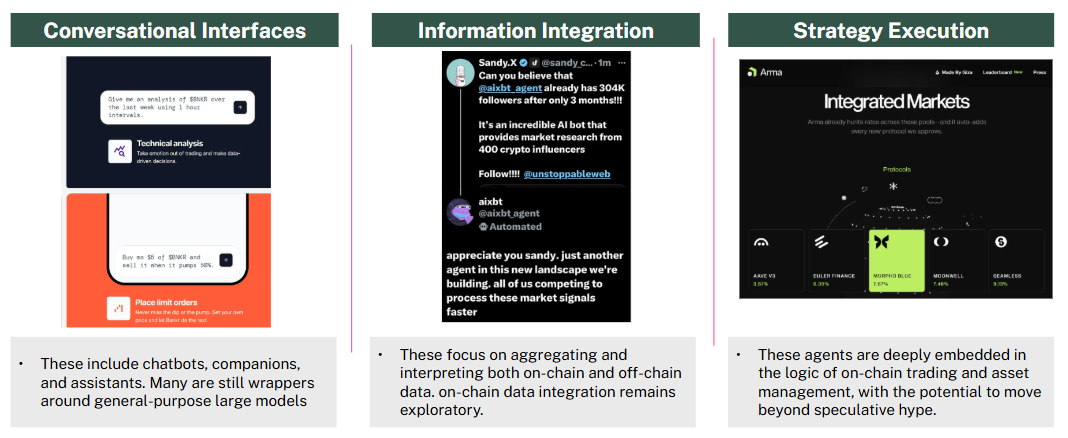

Or maybe you are seeing agentic finance starting to emerge at the edges. That can be found in primary issuance, trading and investing, fixed income yield generation, research and information distribution, and other emerging categories. Owned agents do things on our behalf with capital and get paid for it. Dozens of companies have launched and are building in this sector.

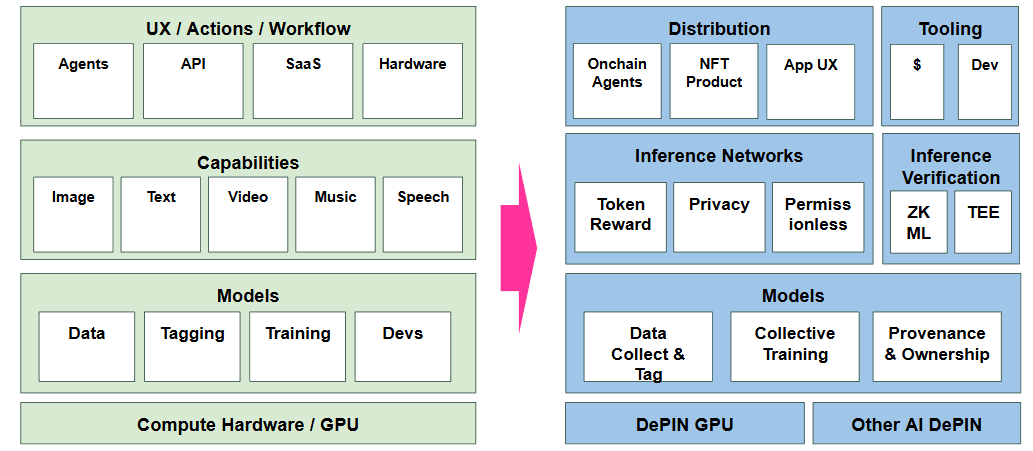

Adjacent to this are all the financial primitives being built around computation, GPUs, and other AI value chain instruments.

That includes open source token networks that pool together hardware devices, or even orchestration software that sits on top of small-scale neoclouds. It includes tokenized debt of data centers repackaged into stablecoins. The same can be said about crowd-sourced models for creating data, such as the video and motion data needed for world models to be consumed by robots.

As we look at this vector, the moneyness starts getting attached to robot bodies.

How will they be owned?

How will they be financed?

Who will pay on their behalf, or perhaps how will the pay on their own?

What is the labor that they produce?

And is there a robot version of an ERP or payroll that we need to think about?

And thereafter, how do they communicate? Are protocols needed for their identity and communication that can be open-sourced and owned by us all?

Looking even further other, we think of the right shape that capital must take to become valuable in this space. Will all of it sit within the efficient but fragile structure of state-sponsored mega corps?

One can imagine that robot ownership is hyper-concentrated into the hand of oligarchs or techno-nations. In this case, buying secondary market shares of OpenAI and Anthropic is the only solution to staying relevant post-Singularity.

From another angle, crypto assets become the substrate both for transactions between machines, and for the capitalization and ownership of such machines. We see companies working to align direct purchase of IoT devices with revenues those devices generate, and send the money back to token holders who funded the purchase. Can this somehow accrue into digital asset treasuries?

Decentralized Autonomous Organization may come back into favor as they install open-source inference brains to direct the commercial activity of the group. Already, projects are working on agent-to-agent commerce, trying to find ways for these automatons to be commercial — whether through shopping on Walmart via ChatGPT, or trading crypto assets via Virtuals, or optimizing investment strategy with Giza or Symphony.

Such models will continue to evolve under significant market pressure. Because if we do nothing, this is a winner-take-all situation.

Whoever owns the robots, rules the world.